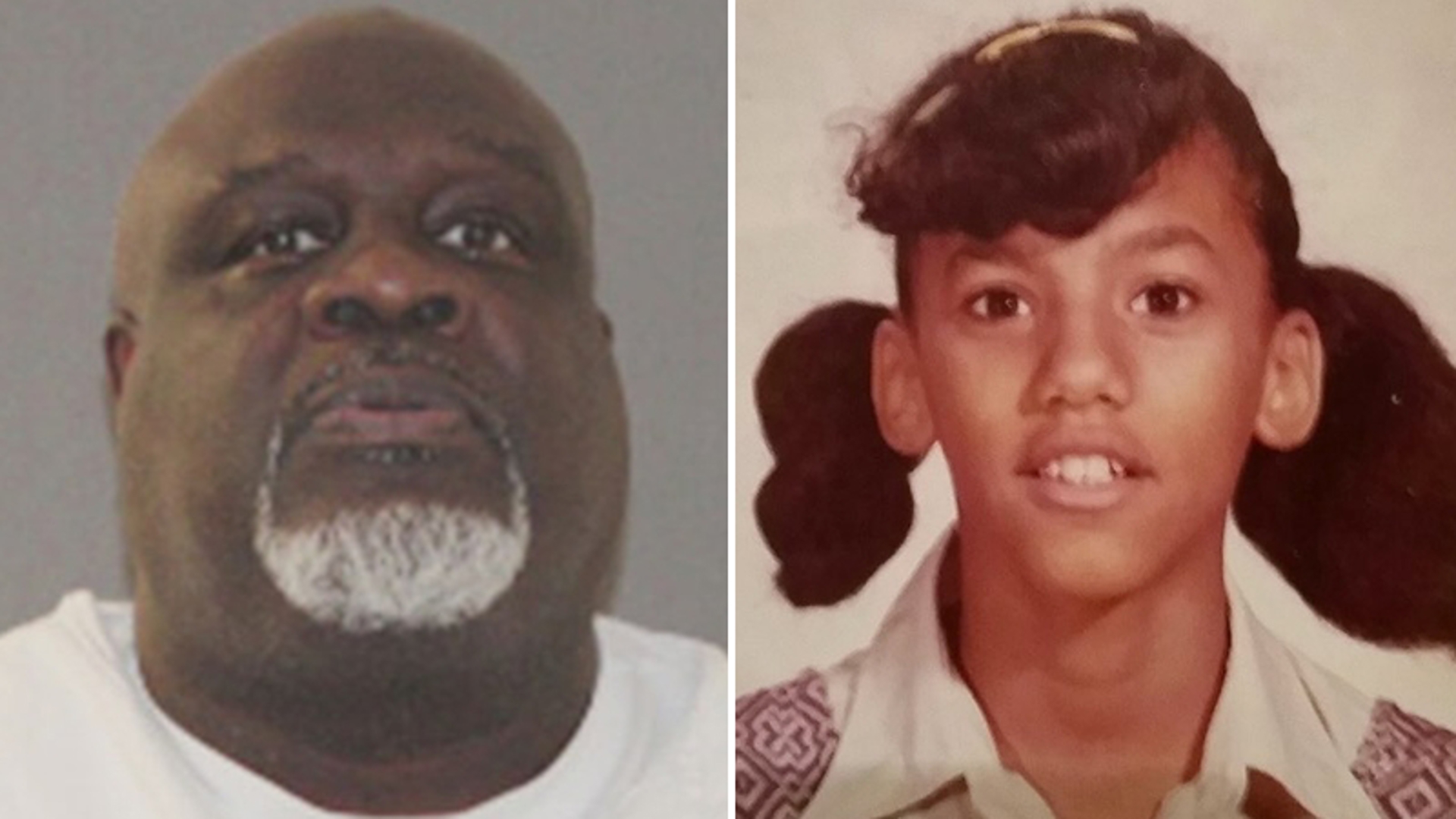

Garcia Glen White apologized profusely to the family of Bonita Edwards and her twin girls Tuesday — but the family wasn’t there to hear his words or witness his execution by lethal injection.

The 61-year-old Houston man professed his remorse for others he had wronged as he uttered his final words at the Huntsville Unit, more than 28 years after a jury convicted him in the 1989 deaths of twins Annette and Bernette Edwards. The jury heard evidence in 1996 about other killings authorities accused him of — a neighbor, Greta Williams, found in 1989 rolled up in a carpet, and a corner store clerk, Hai Van Pham, in 1995.

“I’m sorry for all the pain I caused anyone,” White said. “I just ask you to please find comfort and closure in your heart.”

He next sang a gospel song, at times tapping his restrained hand and foot to the rhythm. He then thanked the prison guards he knew for “treating us like human beings.”

Texas Department of Criminal Justice spokesperson Amanda Hernandez said White would not have known who was on the witness list for the victims before the execution.

The lethal dose began at 6:39 p.m., and his breathing appeared to cease within two to three minutes. He was declared deceased at 6:56 p.m. He had no friends or family present during the execution, a choice that he made, his attorney said.

White spent three days leading up to the execution talking with visitors and other incarcerated people, according to a report of his activities compiled by TDCJ officials. On Saturday night, as a federal court mulled a potential stay — he prayed.

He wrote from his Polunsky Unit bed late Monday and stayed awake for most of the night, packing up his cell and reading, according to the report.

A state district court judge recently rejected his plea to rescind the warrant scheduling his death to make time to review a potential intellectual disability claim. Elsewhere, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals denied a swath of last-minute legal challenges by White’s attorney, calling them too late and lacking in merit. Several appeals with the U.S. Supreme Court were rejected in the minutes before White’s execution warrant was scheduled to take effect.

District Attorney Kim Ogg met with relatives of Pham and Williams before observing the execution alongside them. After the country’s highest court denied White’s attempts to stay his death, she told the family that he was to meet “one more judge,” alluding to God.

Ogg said she had also been in contact with the Edwards family.

After the execution, Ogg pleaded for changes to the length of time and number of times death row inmates can appeal their cases to state district and federal courts to alleviate families from having to wait decades for their loved one’s killer to be put to death.

“If you’re going to have the death penalty and continue to execute people in Texas, we have to do something to help these families get to the end,” Ogg said.

Ogg said White, a former college football player and one-time fry cook, was considered by a grand jury in 1989 — under former district attorney Johnny Holmes — for the death of Williams, but they chose not to indict him. The Edwards children, both 16, were killed later that year amid a drug-related argument with their mother. The DA said evidence at the time suggested White may have sexually assaulted one of the children.

Their north Houston case went unsolved until 1995, when authorities also linked White to the additional deaths. A jury only found him guilty of killing the twins.

Court records show White’s lawyer, Pat McCann, collected several recent affidavits from friends and family saying White had an intellectual disability, but they spent years protecting him by thwarting a thorough review into that claim. He had an education level of 13 years, according to TDCJ records.